Museums are full of historical photos of early Fort Collins – like the Old Main building on Colorado State University’s campus and Old Town when it wasn’t considered “old.” But there’s a lot more to Fort Collins’ history before the city’s founding in 1864.

Between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago, ancient peoples traveled to the Front Range, following the migrations of animals, and set up camps.

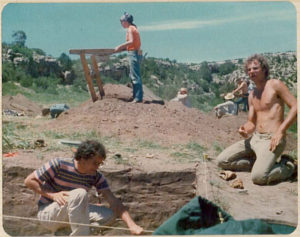

And since 1969, students attending the CSU archaeology field school have been researching the lives of these past peoples, as well as learning valuable archaeological skills that set them apart from other anthropology students.

“The CSU Archaeology Field School has a reputation for producing quality, job-ready archaeologists,” says Emma Zink-Hatcher (MA ’16). “Experiencing the field school first-hand, this reputation is entirely founded. Beyond this research experience, the personal experiences add another level of value for students as they discover new talents and develop a fresh perspective on Cultural Resource Management (CRM) and archaeology in a constantly changing world.”

Summer 2018 marks the 50th archaeology field school, led by former participant and Associate Professor of Anthropology, Jason LaBelle (BA ’95).

In the field school, students engage in a seven-week, hands-on experience during which they learn all facets of archaeological method and theory in the great outdoors. Students – both undergraduate and graduate – must apply to attend the field school and are selected by the instructor on a competitive basis. The field school consists of two summer courses: a one-week course in the classroom that introduces them to the methodology and materials that they will encounter in the field, and a six-week course where students conduct survey, shovel testing, and excavation at various locations throughout Colorado.

“The CSU archaeology field school is the most important class I teach,” says LaBelle. “Over a short seven weeks, students put the book learning behind, and gain valuable experience in “dirt” archaeology. They come back to campus as better students – engaged, excited, and focused on their courses as the content makes much more sense given they’ve experienced archaeological methods and theory first-hand.”

The beginning of CSU archaeological training

The original goals of the field school were threefold: to provide an opportunity for students to gain hands-on experience that they could then leverage for employment; to learn about the history and prehistory of the western Great Plains; and to conduct fieldwork outside in beautiful landscapes. Jim Judge, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Fort Lewis College, taught the first two CSU archaeology field schools. The crew excavated Roberts Ranch Buffalo Jump near Livermore, as well as the Fort Vasquez trading post near Platteville.

Emerita Professor of Anthropology Liz Morris took over the field school in 1971. For 14 years, “a succession of [her own] Volkswagen vans shuttled students on field trips through the Southwest and Rocky Mountains, sometimes touring archaeological sites but more often engaged in research,” described archaeologists Kelly Pool and Mike Metcalf (BA ’71, MA ’74). However, “while Liz ferried her students across the West on field trips, her priority with field schools was to make them local and accessible to all students,” Pool adds.

Metcalf was part of Morris’ first and second field seasons when they excavated the T-W-Diamond tipi ring village on Roberts Ranch, and Dipper Gap, a stratified site in northeastern Colorado, that became Metcalf’s thesis work. T-W-Diamond consists of 1000-year-old stone circles and was used seasonally for hunting, butchering, and collecting activities. Occupied during four different cultural periods from B.C. 1655 to A.D. 800, Dipper Gap functioned as a campsite for prehistoric peoples “hunting and foraging in an ecologically diverse region of the Plains,” describes Metcalf.

Laboratory of Public Archaeology

The 1970s were an important time for archaeology as well as the field school. Emeritus Professor of Anthropology Russell Coberly in his article, Recollections of Early Anthropology at Colorado State University and Reflections on Anthropology, explained, “In the 70s, federal laws mandated that public lands be surveyed for cultural resources prior to their exploitation for various industrial, commercial, and extractive purposes.” Emeritus Professor of Archaeology Calvin Jennings joined the department in 1972 and started the Laboratory of Public Archaeology (LOPA) as an active contracting program to fill these mandates. In addition to managing LOPA, Jennings helped co-direct the archaeology field school from 1973-79 providing further opportunities for student research.

“I really liked being able to work with the students, bring them along as developing professionals, and see them move along to pretty good careers,” says Jennings. “They were on the ground doing professional work – learning to do the data collection and interpretation. Their writing projects then went to the clients.”

Today, Archaeology Collections Coordinator Jeannine Pedersen-Guzman and LaBelle curate the collections housed in LOPA, now known as the archaeology repository. Most of the collections are from the CRM projects associated with LOPA and some are from the CSU archaeology field schools.

Revisiting Bull Draw

In the mid 1970s, the Bureau of Land Management asked LOPA to investigate the Bull Draw Shelter site in northwestern Colorado, because pottery hunters had vandalized it. Jennings took a crew of about 10 undergraduate and graduate students to Bull Draw, discovering a buried granary and several storage pits. In 2016, LaBelle took students back to this remote portion of Moffat County in order to investigate these 1000-year-old Uinta Fremont granary sites in the Skull Creek Basin and surrounding lands. The CSU field school will return to Bull Draw in the summer of 2018, building on the work undertaken by Jennings some 40 years earlier.

“The canyon system was full of rock shelters and granaries to store corn, as this was a culture that seemed to be experimenting with horticulture as a complement to hunter-gatherer activities,” explains Zink-Hatcher. “The outwashes of the canyons had pit houses and tool manufacturing sites, and the upslopes had many tool manufacturing sites. At the cave, we were able to document the extent of looting that had occurred in the 1940s, as well as uncover another potentially collapsed granary. The area seemed to be a rich settlement, though there is some evidence of people protecting this territory, suggesting that not only was more time spent here than at Fossil Creek [mentioned below], but people were returning as evidenced by extensive storage in hard-to-reach areas on the canyon walls.”

Student experience

The mission of the archaeology field school remains similar to its founding: to give students the opportunity to apply what they have learned in the classroom out in the field, getting them outside, where they collect data, and analyze those data in order to understand how past peoples lived.

“A good field school lays a solid foundation for students learning research design, how you apply it, and how to adapt it,” says Metcalf. “In addition, they find out if they are cut out for fieldwork. My fieldwork certainly did. It reinforced that I wanted to be an archaeologist.”

Professor LaBelle agrees. “Sometimes it is hard for students to visualize archaeology as a career. But the field school gives them that opportunity — so that students can see what it would be like, what they might do to make a living in this field, and to satisfy their intellectual curiosity about the distant past. In designing the field school work sessions, I take into consideration the knowledge, skills, and abilities that students need to know as a practicing archaeologist and we put these into action during every week of the field program.”

During the 2018 field season, LaBelle and his students will be excavating at Fossil Creek, a major prehistoric campsite located in southeast Fort Collins, for the third year in a row. “We now have artifacts and radiocarbon dates from the site stretching back to the Ice Age,” explains LaBelle. “Our excavations primarily focus on the last 1500 years, where we now have unearthed portions of a major camp littered with over a dozen hearths/fire pits, broken pottery, shell beads, animal bones, and loads of stone tools.”

When LaBelle was hired by CSU, he and Liz Morris visited her old field school sites in northeastern Colorado. As Pool relates, “except for Dipper Gap [mentioned above], Liz held all field schools within an hour’s drive of Fort Collins so that students could get there and back in an eight-hour day. She said she knew many of her students had spouses, apartments, plants, or even night jobs, which especially impressed her.” Pool and Metcalf noted that Liz often “marveled that current CSU students were still conducting research built around her initial explorations and greatly benefiting from better access to permissions, lab space, and new analytical methods.” Jennings echoed her sentiment that the field school is still going strong and under great leadership decades later.

“Through Dr. Morris, I learned the art and science of site survey…from observing how she interacted with ranchers, to learning site survey techniques and how to record sites,” adds Dave Swinehart (’75). “I can still recall the rides to the project in her Volkswagen bus, the anticipation of discoveries yet to be made, and the beautiful high plains landscape.”

For five decades, outstanding professors such as Liz Morris, Cal Jennings, Jeff Eighmy, Larry Todd, and Jason LaBelle have had profound impact on both students’ experiences at CSU and their careers. Students participate in hands-on activities outside of the classroom connecting theory to reality, textbook to real life. It is through these learning opportunities that students go out into the world with the knowledge and skills that make them competitive in the industry.

Last year, generous alumni and friends funded this summer’s Anthropology Field School Scholarship, enabling five students to participate without financial burden. Alumni and friends can support even more students this year thanks to Dr. Jeff Eighmy, professor emeritus and chair of the Department of Anthropology, and his wife, Catherine, who have pledged to match all gifts up to $2,500! Through the power of collective giving, a total of $5,000 can be raised for the Anthropology Field School Scholarship. Give online today: https://giving.colostate.edu/anthropology