A daughter’s promise

Northern Arapaho collection comes home to Northern Colorado story by Jeff Dodge published May 3, 2021Before he died in 2018, Mark Soldier Wolf reminded his daughter to keep her promise.

Yufna Soldier Wolf had promised him that the vast collection of historical documents regarding the Northern Arapaho he had amassed over his lifetime would be preserved, returned to their homeland, and made accessible to relatives, the tribe and possibly the public.

Mark Soldier Wolf was a descendant of a long line of chiefs who led the Northern Arapaho when its home was Northern Colorado, and his great-grandmother participated in the Battle of Little Big Horn. He had been involved in repatriation initiatives over many decades, from the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 to a successful effort in 2018 to bring home the bodies of his uncle and other young tribal children who died at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where they had been taken in the 1880s to be forcibly assimilated into U.S. culture.

Yufna Soldier Wolf says her father’s legacy was serving as a tribal historian. The U.S. Marine Corps veteran meticulously documented and saved everything he could about the tribe. There are tintype photos, records of his family’s military service, notes he took at meetings, and various Arapaho recordings. Mark filled many notebooks with material for the book he was writing about the history of his people. Yufna says her father remembered taking wagon trips to Fort Collins and Estes Park as a small boy, listening to his grandparents tell stories along the way.

Mark Soldier Wolf

Other materials

Over the course of about 14 years, Yufna and her sister went through all of the materials with their father, organizing and labeling them. Among the items is a cardboard pattern of Mark’s right foot and the kit he used to make his moccasins, as well as a large scroll containing a family tree. In addition, there are accounts of the tribe’s former Northern Colorado home, including maps with Northern Arapaho names of important archeological and geographic features, information about constellations, and ecological records of the region’s animals and plants.

Those include the Council Tree, a 120-year-old cottonwood that used to stand in southeast Fort Collins near the Cache La Poudre River. According to Yufna, the tree was used primarily as a place for the leaders of the 13 Arapaho bands in the area and other tribes like the Cheyenne, Lakota, Dakota and Nakota to reconnect and catch up.

The problem for Yufna was that this rich archive of her people’s history was being stored in 55 plastic boxes in a trailer near their home on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming — not exactly a secure location for her father’s precious materials.

Mark Soldier Wolf died on Nov. 9, 2018, at the age of 90, and his will specified his wishes for the collection.

“Before he passed away, he told me, ‘You know what your mission and your job is,’” Yufna recalls. “His biggest goal was to get this all back to the ancestral homeland, the Council Tree area.”

Yufna Soldier Wolf with boxes of her father’s historical materials. Photo by Jared Orsi

Fortuitous introduction

In 2019, when film producer Frank Boring was working on a documentary about the history of Colorado State University to commemorate its 150th birthday, he wanted to interview a prominent Native American whose people inhabited the land on which the University sits. He turned to CSU alumna Jan Iron, a member of the Navajo Nation and longtime employee at the CSU Agricultural Experiment Station, who has served for decades as president of the Northern Colorado Intertribal Powwow Association. Iron introduced Boring to Yufna, former director of the Northern Arapaho Tribal Historic Preservation Office in Riverton, Wyoming. The two families had become close after attending powwows together in the 1990s.

When Yufna was interviewed for the documentary in fall 2019, she mentioned her father’s collection to Boring and Jared Orsi, a professor in the Department of History who was also interviewed for the film. Coincidentally, the Public Lands History Center that Orsi directs had just been awarded a three-year, $225,000 grant from the Luce Foundation for a project called “Telling Untold Stories.” He realized that he could direct some of that funding toward efforts to preserve the archive and make it accessible.

“These are more than inanimate objects for Yufna and her family,” Orsi said. “They are a passageway to connect with people who are no longer here.”

He added that the collection will be an incredibly valuable resource for preserving the culture and history of the Northern Arapaho.

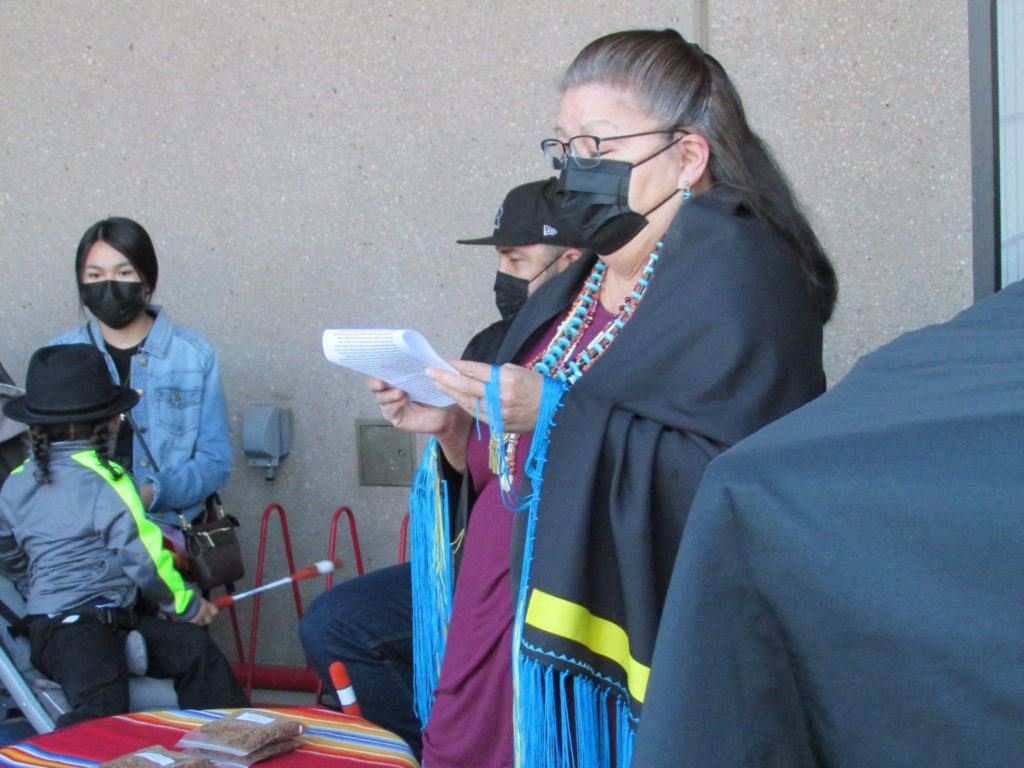

Yufna speaks to a campus group during her visit to CSU in fall 2019 to be interviewed for the sesquicentennial documentary. Photo by William A. Cotton

A history threatened

Over the ensuing months, Yufna stayed in touch with Boring, Orsi and Ed Warner, who served as executive producer of the sesquicentennial documentary and is a longtime CSU donor and alumnus of the college that now bears his name, the Warner College of Natural Resources.

In August 2020, Boring and Warner visited Yufna and her family on the Wind River Reservation to see the collection.

“It was amazing how we were welcomed by the Soldier Wolfs,” Warner recalls, adding that the family insisted on cooking meals for them. “They wouldn’t let us eat out in a restaurant. We were able to connect with the entire family, three generations.”

Toward the end of their trip, a grass fire erupted not far from the trailer, and while firefighters extinguished the blaze, it created a sense of urgency to move the archive to a safer location, since such wildfires are not uncommon.

“We realized it could go up in flames, and there goes our whole history,” Yufna says.

“It made us realize that we had to do something soon,” Boring adds.

The wildfire that broke out near the trailer in August (left) and the section of siding that was ripped off the trailer by strong winds earlier this year. Photos by Frank Boring and Jared Orsi

Heightened sense of urgency

Then, in early 2021, strong winds from a winter storm stripped a large section of siding off the mobile home, prompting Yufna to contact her CSU partners and put the relocation of the materials on the fast track.

“I didn’t want to see it blow away or get lost in a fire,” Yufna explains. “A lot of those things are priceless.”

“It really told us how at risk this whole collection was,” Warner adds. “The good news is that nothing was destroyed, and it mobilized us.”

After initial talks with the Denver Museum of Nature and Science and History Colorado, they selected the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery as a suitable temporary home for the archive.

Lesley Struc, who has both a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s degree in public history from CSU, serves as curator of the archive at the museum and had worked with Boring on the documentary. She and other museum leaders, like fellow CSU alumna and Director of Community Connections Shannon Quist, agreed to house and begin processing the collection as part of a one-year loan, while the CSU group works with the family to secure a permanent home for the archive.

After a send-away blessing performed by Yufna Soldier Wolf, all of the boxes of materials were loaded into a van, and Yufna signed paperwork for the museum — with her mother looking on from the window. Photos by Jared Orsi

The relocation

In late February, Boring, Warner and Orsi drove to the reservation, taking a van that could accommodate the entire collection. After packing the van with the boxes of materials, Yufna signed museum paperwork and said a send-away blessing over her father’s collection, observing COVID-19 precautions as her 85-year-old mother, Florita, looked on. Boring says Florita told the group in Arapaho, with Yufna translating, that this was a long time coming, and that it fulfills a commitment she made to her late husband.

“She was just glowing,” says Boring, who now works for Rocky Mountain Student Media and plans to make a new documentary about the entire experience. “You could see how happy she was. It was a great moment.”

When the van arrived at the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery on March 1, it was greeted by a crowd of museum employees.

“I think everybody was quite moved by it,” Warner says. “I think having that turnout was very validating for the Soldier Wolf family.”

“It was so special,” Struc adds. “When we received this loan, it was so meaningful for me and all who were there.”

“It was probably the biggest presence we’ve ever had at the museum for the arrival of an archival collection,” says Quist, who holds a CSU bachelor’s degree in the social sciences.

When the van arrived at the museum, the materials were unloaded, and Jan Iron performed a welcome blessing, accompanied by drumming and singing by her son, Zach Rockwell, and grandson, Lorenzo Rockwell. Photos by Jared Orsi

A homecoming ceremony

Among those present when the collection arrived was Jan Iron, who had introduced Yufna to Boring. At the request of the Soldier Wolf family, Iron and her son agreed to perform a blessing to welcome the collection back into the ancestral home of Northern Colorado.

At first, Iron was unsure whether it was appropriate for a Navajo — and a woman — to lead the welcome-home blessing for Mark’s collection. But Yufna assured Iron that her mother wanted Iron to stand in for her because she was unable to make the trip. Iron did the welcome blessing while her son, Zach Rockwell, drummed and sang. Rockwell’s young son, Lorenzo, helped with the drumming.

“I was honored and humbled to do it,” Iron says of the blessing. “With the respect and love I have for Yufna’s mother, Florita, I couldn’t say no. And this collection has first-person accounts of this land. It means everything to us.”

“I feel better knowing that it’s safe in Fort Collins,” Yufna concludes. “Hopefully some good comes of it, once it’s digitized and made available. This is my father’s legacy — he wanted future generations to know about the Arapaho people, especially his grandkids, other relatives and tribal members.”

And now, she and her CSU friends are well on their way to fulfilling the promise she made to her father.