Editor’s note: This guest column was written by students Todd Newhouse, Dalton Haraway and Merry Gebretsadik as well as Assistant Professor Dominik Stecula regarding a report they wrote on information disorder as part of a political science capstone course.

The 2016 Presidential Election has put the spotlight on “fake news” and a concern about false and misleading information spreading like wildfire on social media, impacting American society in various ways. Although the problem itself is as old as the republic, the Internet and the importance of social media made the problem seem overwhelming. As the same time, the term “fake news” has lost any analytical meaning and devolved into a partisan insult of sorts. To fully understand the problem, therefore, it is important to look beyond the simplistic nature of “fake news.”

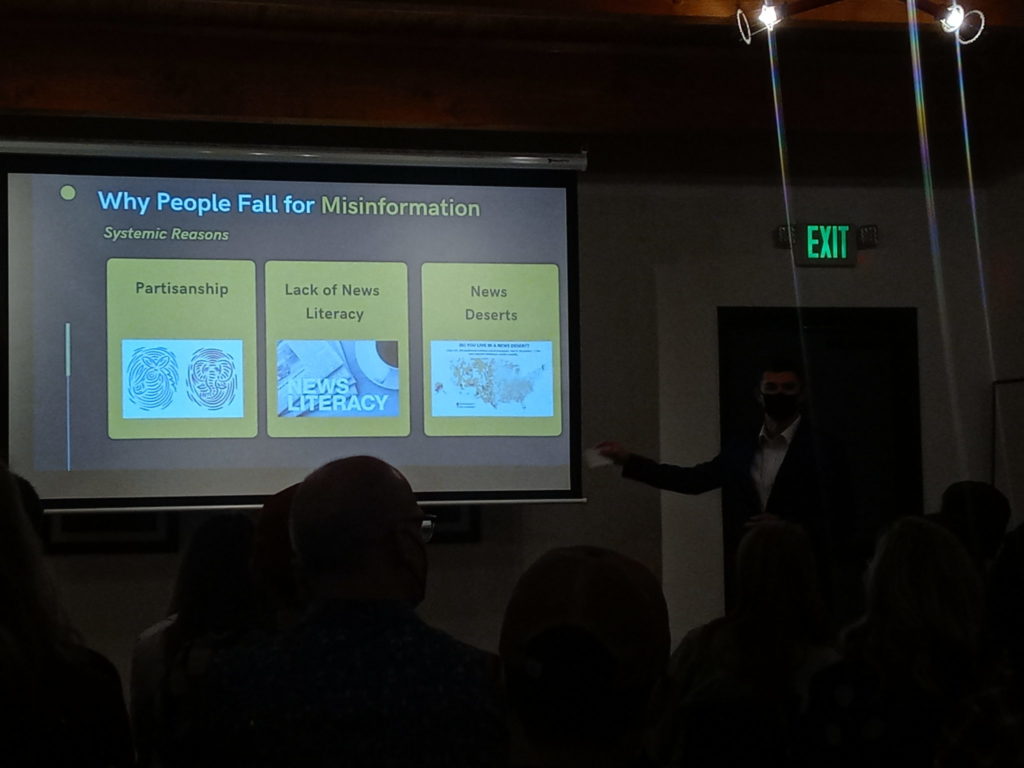

Our point of departure is Information Disorder, which refers to the many ways our information environment is polluted. Information Disorder has three main components: Misinformation, Disinformation, and Malinformation.

Misinformation refers to false information that is not created or shared with the intent of causing harm, but is untrue or misleading, nonetheless. Propagators of misinformation are typically unaware that the information they are sharing is false. Disinformation is any false information that is created and/or shared despite it being knowingly untrue. Individuals or groups that spread disinformation typically have malintent or motive for doing so. In fact, they can be driven by certain ideological or political commitments, profit, or are deliberately intending to cause harm. Malinformation is truthful information that is shared with the intent to cause harm. An example of this can be demonstrated through the hacked emails released from the 2016 Democratic National Convention and the Hillary Clinton campaign. The information contained in the emails may have been true, but their release and spread were motivated in part to smear the DNC and Clinton.

The degree to which our information environment is polluted sometimes overwhelms people and occasionally motivates defeatist attitudes. But it is important to understand that as citizens, we’re not helpless against Information Disorder, and that we can take meaningful actions to ensure the information we engage with is reliable. As a class, we thought extensively about what steps a citizen can take to battle Information Disorder in their information environment.

Steps to Battle Information Disorder

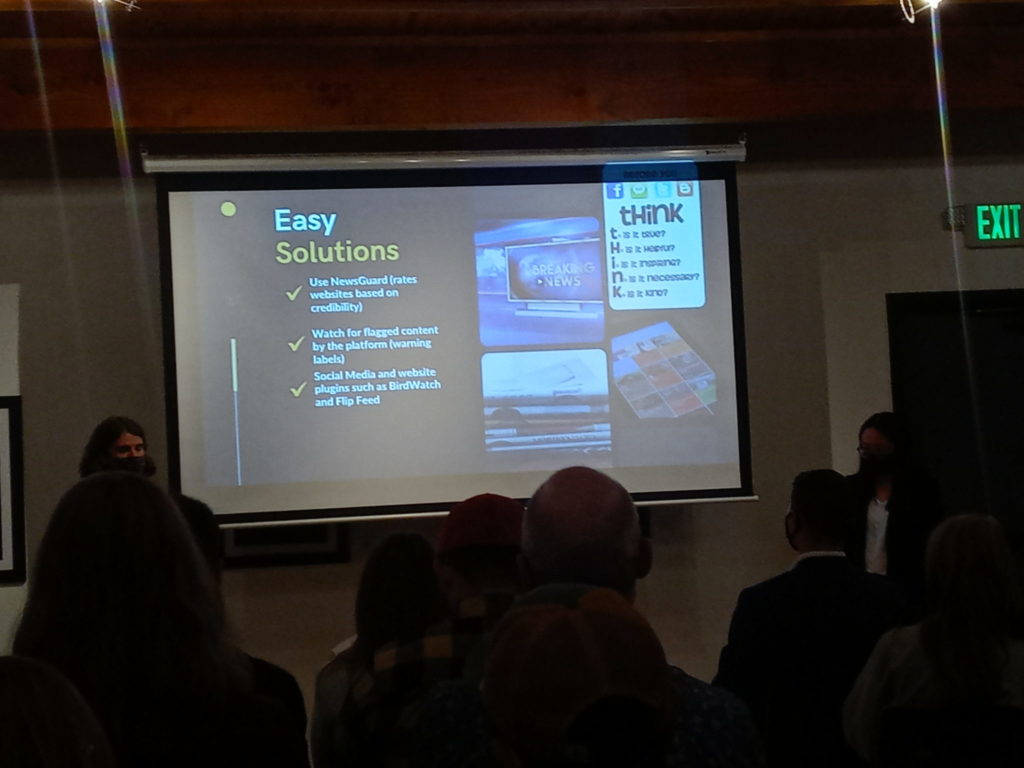

Look for fact check warnings on social media.

Posts that have been reported for containing false information typically receive some sort of label from a given social media platform. Information that has been flagged should be consumed with a heavy amount of skepticism, if at all.

Utilize reliable local news

Local news is typically closer to the source of home-grown news and usually contain less focus on polarizing culture war issues that animate national and cable news.• Avoid open forum sources disguised as news. Anonymous and unaccredited authors should never be viewed as reliable, no matter how believable their information may seem. If you do not know who is writing it, be skeptical of it.

Pause and do further research before sharing on social media.

Become well informed before sharing information on social media, utilizing an array of sources and viewpoints (if applicable). If the scope of your knowledge comes from one post, or you could not reasonably answer any follow up questions about the topic, you are probably not informed enough to post on the subject.

Gather information from news sources across the political spectrum.

Subject yourself to different perspectives, from across the political spectrum. It is easy to do with tools such as AllSides or The Flip Side.

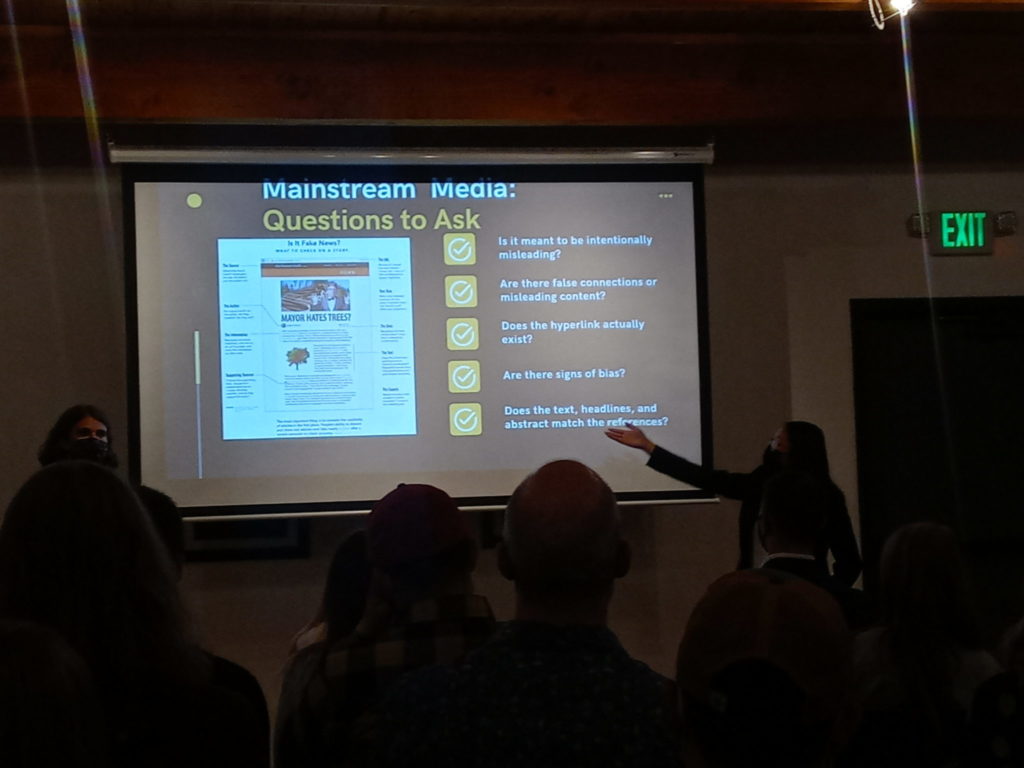

Google headlines that seem outlandish to see if other sources are reporting about the topic in a similar fashion.

Media outlets frequently create headlines that are sensational in order to generate more views and clicks. If an article or headlines seems like it is trying to garner an emotional response from its reader, it is worth double checking the story and perhaps utilizing a different source.

Report misinformation and disinformation when you see it.

Being a responsible digital citizen means not only consuming information, but reporting things that are harmful. Every social media platform has a built-in reporting mechanism designed to help users flag misleading or false content. Use it.

Have healthy and respectful conversations with people that disagree with you.

Have conversations without the end goal of convincing or ultimately agreeing but understanding where someone with different beliefs is coming from. We will never all hold the same beliefs but asking questions and respectfully engaging with others while keeping an open mind will ensure that you can learn something new.

Utilize browser extensions that challenge your social media algorithms and verify reliability of websites you visit.

Various browser extensions, such as NewsGuard, can help prevent the influence of misleading information while surfing the web.

Read full articles, not just headlines.

Headlines are often sensationalized or editorialized to help lead to more views and clicks. However, the article itself may tell a different or more in-depth story.

It is important to acknowledge that being a well-informed digital citizen is a responsibility that we all have. While holding different views and opinions, even those that are objectively false, may seem like an uninfringeable right, these beliefs held in mass have real consequences for society. Whether it be COVID-19 misinformation leading to vaccine hesitancy or political disinformation leading to the storming of the Capitol, our interconnectedness ensures that misleading information no longer affects individuals in a vacuum. As a result, everyone should aim to be a responsible digital citizen and do their part to make sure our information environment is less polluted.

This article is based on a semester’s work of political science seniors in Prof. Dominik Stecula’s Capstone “A Citizen’s Guide to Navigating Information Disorder.” The students, who, along with the authors of the piece included (in alphabetical order) Gavin Alsop, Emily Baller, Olivia Barden, Denver Bridges, Rachel Cummings, Alec Eyl, Ellie Gilchrist, Jamie Greene, Megan Heesemann, Jackson Hunter, Addy Johnson, Ben Keyes, Ethan Lee, Joe Rusert, Riley Sanders, and Jose Silva Rodelo, have produced a full-length report on Information Disorder and dealing with it.