Story by Jennifer Clary

This week the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art is opening a new installation consisting of reassembled 3-D prints of real homes, all lying within 100 feet of active hydraulic fracturing well pads in Weld County.

This week the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art is opening a new installation consisting of reassembled 3-D prints of real homes, all lying within 100 feet of active hydraulic fracturing well pads in Weld County.

The exhibition, “Case Study: Weld County, CO,” will be on display in the Griffin Foundation Gallery at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art Oct. 5 through Dec. 15. General museum hours are Tuesdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. – 6 p.m., and all programs are free and open to the public. The museum is located in the University Center for the Arts at 1400 Remington St.

A talk and opening reception with artist David Brooks takes place at the museum on Thursday, Oct. 5, at 5 p.m.

About Brooks

Brooks is known for an artistic practice that considers the relationship between individuals and the built and natural world, while questioning how nature is perceived and utilized. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in both solo and group exhibitions that examine the environment and sustainability. The artist has a Master of Fine Arts from Columbia University and works in New York City.

Brooks visited CSU in fall 2016 to work with Professor Erika Osborne’s Art and the Environment class. He accompanied them on a field trip to examine fracking sites and their proximity to homes, schools, churches and playgrounds in Northern Colorado. The work in this exhibition responds to that trip and to the high incidence of hydraulic fracturing throughout our state.

Fracking in Weld

Weld County, which arguably has the densest number of active fracking wells in the country, lacks visual evidence of what lies beneath its comfortable suburban life, according to Brooks. A map illustrating the underground network of active gas extraction lines reveals a sprawling, tightly knit mesh of export pipelines sitting just below the masterfully crafted image of normalcy, he says. Brooks explains that this super infrastructure is something usually placed deep in the desert, under the ocean, or otherwise marginalized to limit human contact, but in Weld County, the domestic and the everyday come in intimate proximity to the industries of resource extraction.

For Brooks, how we see the landscape is a reflection of the guiding ideologies of our distinct time and place. Case Study’s image scans were taken only from what was observable from a pedestrian’s point of view, from sidewalks, roads or public paths. This restricted approach to the scanning process presented anomalies within the modeling program. When the consecutive images were assembled to form a 3-D model, the software unpredictably supplemented missing information or omitted existing information. In some cases, the sky folded into rooflines and exterior space was mistaken for interior space.

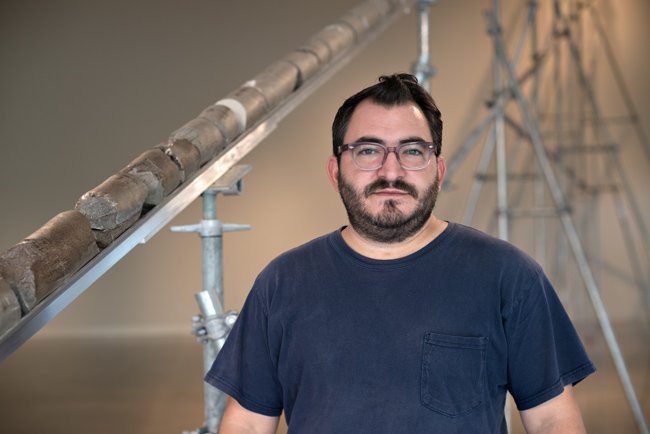

David Brooks

For the artist, such deformations make evident the disconnect between our actions and how we perceive them. However, while Brooks may be critical of many modes of resource extraction, given the adverse impacts that he has witnessed around the world, the exhibition itself is only intended to raise questions and prompt discussion about the proximity of hydraulic-fracturing sites to our inhabited structures.

“The exhibition does not take a position on the issue, per se,” says Lynn Boland, director of the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art. “Rather, it attempts to provide a new perspective on existing data in order to allow viewers to have a more informed opinion.”

Stimulating conversation

For Boland, the visual arts as a catalyst for information gathering and conversation about current issues is a critical component of museum activity.

“Art can open up the dialogue about issues that matter, allowing people to ask questions as a single piece offers a multitude of perspectives,” he said.

For Brooks, the exhibition as a sculptural study is key to the discussion.

“A study is not a final result,” he says. “It is not meant to be an end, but rather a means to potential ends at a later time. One may even see it as an act of hope.”

Acknowledgements

Case Study: Weld County, CO would not have been possible without the discerning eyes of art students Emily Boutilier Sullivan and Kyle Singer, and their keen efforts in scanning the houses used as case studies.

This project, part of the Critic and Artist Residency Series, is made possible by the FUNd at CSU and the City of Fort Collins Fort Fund. This project is also sponsored by a grant from the Lilla B. Morgan Memorial Endowment, which works to enhance the cultural development and atmosphere for the arts at Colorado State University. This fund benefits from the generous support of all those who love the arts.