Nine years after the first wave of plague decimated 40 to 60% of Europe’s population at the close of 1351, plague would rear its head again.

Two centuries later, the people of the Iberian Peninsula battled epidemic level diseases like smallpox that would stretch across generations, leaving people exhausted and seeking healing from the emerging and often dueling establishments of medical professionals and religion.

Now in the 21st-century and the third year of a global pandemic, many of us are asking ourselves the same questions that the people of the Middle Ages and early modern era wrestled with as well: How long will this last? How do I stay well? What do I do when I get sick?

“I’m very interested in what people do when they get sick and how they try to understand being ill and how they try to fix it,” said Nicole Archambeau associate professor of history and author of the 2021 book, Souls Under Siege, which focuses on pursuits of health and healing in 14th century Provence, France.

“I’ve been working a lot with religious documents that show the broad spectrum of the ways people understood the world anywhere from spiritual sickness to physical sickness.”

John Slater, a literary and cultural historian in the Languages, Literatures and Cultures department, studies the interplay among medicine, science and religion in the 16th and 17th centuries in Spain and Spanish colonies. Much of Slater’s research analyzes how Iberians of the 16th and 17th century utilized literature to address rising concerns in science and medicine.

“The period that I study, hundreds of years later, people are exhausted. People are exhausted by public health interventions, they’re tired of having their movement limited,” said Slater, professor of Spanish. “I would say that distrust of medicine is really a constant in history.”

Nearly 645 miles and 300 years separate the specializations of Middle Ages historian, Nicole Archambeau, and Early Modern Era historian, John Slater, but there are similarities in the way that people of that time and place thought about illness, pursued wellness and incorporated a variety of modalities to get better.

We invited Slater and Archambeau to sit down and discuss how Europeans viewed health and interacted with medicine – offering insights into what has changed in our own views of health and what hasn’t changed.

How did the people of 14th century Provence/16th century Spain view health, particularly in the face of their biggest disease crises?

Was that authority trusted by the public? What was the response to those authorities providing that oversight?

John Slater

I would say that distrust of medicine is really a constant in history. It’s especially the case in the 17th century because cauterization is such a common treatment for imbalance of the humors.

Traditional physicians and traditional academic medicine in the 16th and 17th centuries believed that the body was composed of four humors and that imbalances in the humors made sickness. People who had sort of an alchemical tendency believed that the body would function, could function perfectly if impurities were removed from it, like blockages and and things that were just keeping the body from functioning the way that it was supposed to.

If you take a hot iron and you press it against someone’s arm, that wound will weep and people will say, “Look at all the bad stuff that’s coming out of you. You really needed this.” But people really didn’t like the pain of being cauterized. They really hated it.

People would be angry about the pain that they underwent, and they would be angry that it didn’t work, and they would be angry that they had to keep scraping together whatever money they had to pay for these treatments.

Part of this exhaustion is reflected in the fact that people who are either poor and don’t have access to a physician or who are frustrated with the health care that they’ve been getting, that dissatisfaction creates a void. During the 17th century in Spain, the church attempts to step into that world.

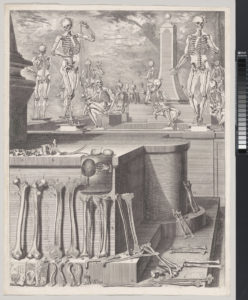

Crisóstomo Alejandrino José Martínez y Sorli Spanish

Plate ca. 1680–94; printed 1740

We are familiar with the production of medicinal drinks like Chartreuse, which is a distilled drink with herbs. Well, Benedictines were distilling all over the place and Carthusian churches were distilling all over the place. And they’re giving these medicines to poor people. Then other folks are interested in buying those medicines. The church starts to realize that that they can have a larger role in the medical system. And so there starts to be more opposition and more conflict between the church and the medical establishment during the 17th century. It’s a real institutional reorientation about the way that these secular and religious institutions are going to interact with one another.

For the most part in Spain, they distilled things like wine, and what you do when you distill something is you just take the most volatile part of the of the wine, which is the alcohol, and if you keep distilling it and keep distilling it, it eventually becomes clear.

People were really interested in the idea that you were getting down to the quintessence of the grape, because all of a sudden you were left with something that was clear that you could light on fire, and that you could put fruit into it, and it wouldn’t rot.

It had all these qualities that made people think that distilled beverages were kind of related to spirituality, and so they were called spirits. It’s the spirit of the grape, what’s left when all the worldly stuff is stripped away.

(John Slater on the distilling of spirits and purifying of the body)

Nicole Archambeau

In the 14th century it [the medical authority] would have been very local, it would’ve been very much the town governments that would have been overseeing their own public health systems.

If we’re thinking about public health from a modern perspective, we’re thinking about sanitation and a kind of oversight of medical care to a certain extent, sanitation was certainly a concern of all these local communities.

We do have some evidence of civic positions, so a city would pay a physician just to stay in that region and treat people on a sliding scale. This individual and this civic position might have some influence.

We see a lot of these physicians writing plague treaties for the whole town when they know the plague is coming.

They can see it on the horizon as it hits the cities nearby. The civic physician of the town wrote the plague treaties that would be translated into a language and read aloud to the local community, “Here’s how to take care of yourself and things not to eat. Here are some ways to take care of what we would now call ‘mental health.”

Some physicians asked that the church not ring the church bells when people died because the constant ringing would really overwhelm people emotionally and this was thought to cause people to get sick. So, the people at the time were seeing what we call mental health and emotional distress as illnesses.

What were the healthcare options available for those populations at this time in Spain and France?

John Slater

There was a real gamut, from knowledge at home to some widely recognized and accepted forms of healing that seem to us today to be very superstitious or even ludicrous.

Everything from lots of home remedies and lots of wise women and folks who knew about herbs and knew what kinds of herbs might make you cough, or make you vomit, or make you go to the bathroom – that kind of knowledge was widely distributed.

There would be charismatic healers and they might have a cleft palate and speak in your face, and by so doing their saliva might sort of baptize you.

There were health professions, so the apothecaries who sold medicine and made medicine and were fully professionalized, and they had a college of apothecaries that would represent them.

There were healthcare professions that look a lot like in terms of their corporate structure, a pharmacist today or an internist today or a surgeon.

What was the role of religion and religious figures?

Nicole Archambeau

Countess Delphine de Puimichel was seen in her community as very holy, and people would try to interact with her as if she were [holy]. They would try to access God’s mercy for healing through her. She did not want to [heal others] because she thought people suffered from illnesses in order to purify their souls — this was her view of what life should be.

People would try to circumvent that and try to receive a miracle from her by grabbing her and putting her hand on their wounds or waiting in a space where they knew she would walk by and grab her clothing or touch her.

John Slater

There is a role that suffering plays in purification, and this is a very old idea; you can find it in the Bible. The suffering that happens to you now will be rewarded in the afterlife, that the meek will inherit the earth, and it’s sort of the essence of the Beatitudes, from the Sermon on the Mount.

People thought that they were being particularly tried, and they frequently thought, especially in the 17th century in Spain, that they are the instruments of God’s providence, and they assume that any obstacle to universal monarchy is a kind of work of Satan.

… there are a lot of folks who will say that this is part of a trial, that we are being tested and that this test is ultimately a little bit like in the case of your saint (Saint Delphine) thinking that people need to go through this, that this is either foretold in Revelation or this is just what must happen.

What can we today learn or glean from people then that might be instructive or useful in our own experiences of illness and pursuits of health and wellness?

Learn more about Nicole Archambeau’s research into health and wellness in her 2021 book, Souls Under Siege available online and in CSU’s Morgan Library as well as her articles, “Penance and plague: How the Black Death changed one of Christianity’s most important rituals,” and “Surviving an invasion during a pandemic in the 14th century.”

To learn more about John Slater’s work, read “Balancing our bodies: how people in early modern Spain approached health and medicine,“ and his collection of essays in “Medical Cultures of the Early Modern Spanish Empire,” soon to be available in CSU’s Morgan Library.