The ski industry in Colorado is a $1 billion a year economic boon, but its history here has been a bumpy one.

With more than two dozen major ski resorts drawing millions of tourists to the state, there’s a cost to all that powder — to our communities and our environment. In his book, Colorado Powder Keg, Colorado State University Associate Professor of History Michael Childers examines the history of Colorado’s ski industry, along with the challenges brought by the industry’s growth — from finding balance within the private development of public lands to the increasing environmental concerns over things like wildlife management and air and water pollution.

Audit host Stacy Nick spoke with Childers about the history of Colorado’s ski industry and what could be next.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

What initially drew you to write about the topic of Colorado’s ski history?

I grew up in a ski town or a town that emerged as a ski town. So, I grew up in the Fraser Valley, downhill from Winter Park ski area. And I started noticing that the ski hill, the ski area, was a much bigger deal than the local ranching community and thinking: There’s going to be a larger story there. With that kernel of an idea, I went off to graduate school to get a degree in history and looking at the evolution of skiing in Colorado and its relationship with the urban corridor. It then grew into this much larger study about the environmental impacts, the politics around the environment and the ski industry in Colorado, starting in the 1930s through the end of the 20th century and into the 21st century, largely along the I-70 corridor.

I want to start with Colorado’s introduction to the ski industry. It had quite a boom-and-bust trajectory in the early days, something that is kind of hard to fathom right now. How did skiing come to Colorado?

The sport really was introduced as we know it in a more modern sense at the beginning of the 20th century with the immigration of folks from Norway and Sweden and Switzerland bringing the sport to Colorado and then people taking it on as a recreational pursuit, largely in the 1910s. So, places like Genesee Mountain outside of Denver was a really popular spot for a long while, Hot Sulfur Springs had some of the first winter carnivals that was induced by a guy named Carl Howelsen, who then moved to Steamboat and helped establish that whole area before returning back to Norway.

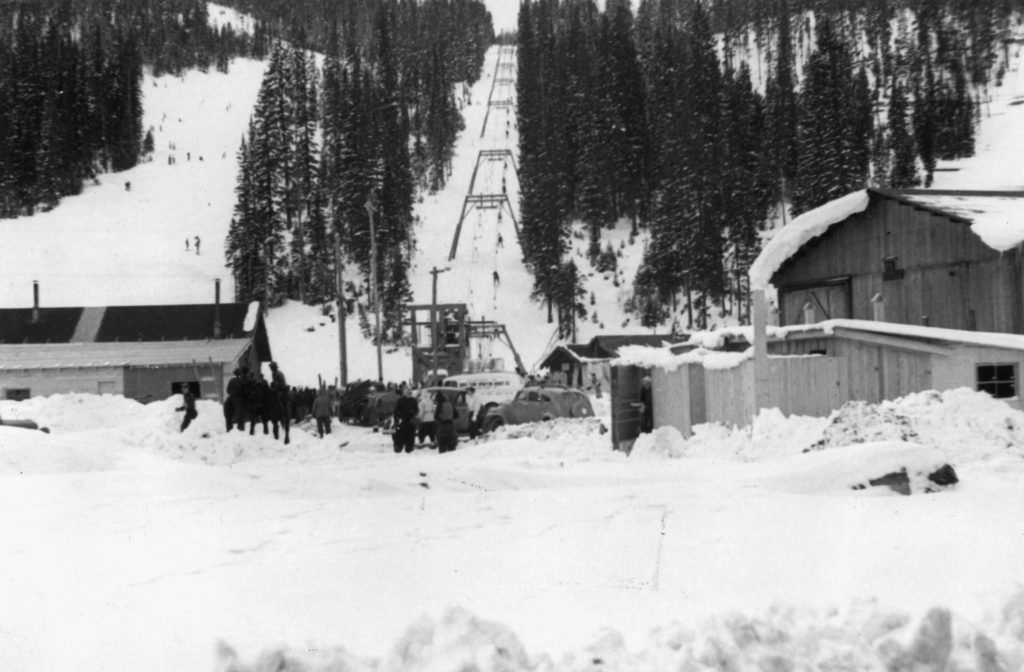

But the sport, as we understand it, with lifts and parking lot and this sort of thing, really hit its stride in the 1930s when you start to see people putting in rope tows on smaller hills throughout the state, places like Berthoud Pass, Loveland Pass, other places throughout the southwestern corner of the state. And it slowly became a mass sport, then a tourist draw by the mid-20th century, following World War II.

For a while there were tons of small ski resorts all looking to be the next Aspen or Vail. There was even one in the 1970s – Sharktooth Ski Area – which was right between Greeley and Windsor if you can imagine that. Why did the majority of these resorts fail?

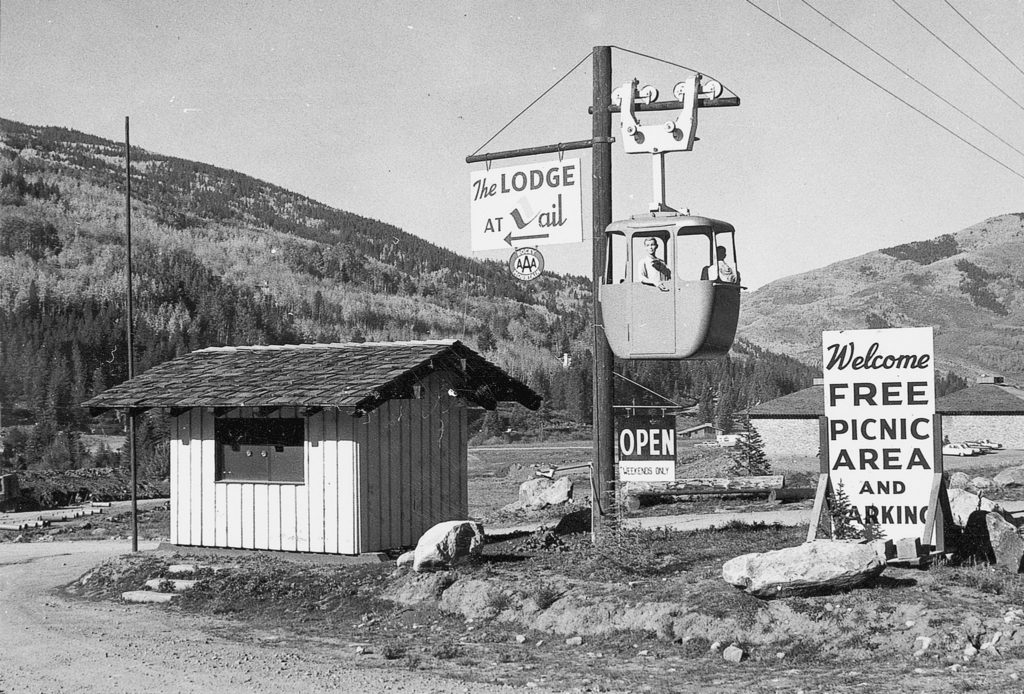

So, you have a boom in these ski resorts like Breckenridge and Vail, and they become the model, right where you have a huge base village and then a pretty substantial amount of ski terrain that’s largely on public lands, U.S. Forest Service lands specifically, and that’s under permit. And that combination requires a lot of money to produce a lot of money. And it worked within Vail and Breckenridge and Keystone and all these mountains. But the smaller ones either never had the capital to get off the ground and succeed or didn’t have good terrain or didn’t have access to Forest Service lands at the scale. So, they just missed one of the magic ingredients to become one of these larger resorts, and so, like a lot of businesses, just ended up folding.

What do you think is going to be the next possible “bust” moment for the ski industry? Is it going to be the drought?

I think so. I think Colorado is in a much safer place than a lot of the rest of the continent, and this includes Canada in that. As the climate continues to warm and change, the predictability of snow, which is the mainstay of skiing, is going to go out the window. But if you look at the larger scope of the Colorado Rockies and really the center of the continent has a lot more consistency in getting snow at certain levels. And so, it’s going to be a little safer financial bet in this region than in New England, which has had a dismal snow this year. Or California, which has way too much snow this year. So that’s going to cause a little bit of a boom and bust with it.

And probably it’s going to be the resorts who can’t invest in infrastructure to adapt to climate change (that end up suffering). So, snowmaking being the big and obvious one and the water rights and the power and energy to make snow in those years with the snow is not, you know, measurable or not very good. The industry, interestingly, has also changed financially in terms of ski passes. So, the Epic and Ikon passes are actually adaptations to this climate change. They’re selling a tremendous amount of them for what is considered affordable, depending on who you are. But they’re selling them before the season, so they already have their money in their pocket before a single lift line starts. So, they’re being responsive toward climate change. For the areas that can’t be in those systems or don’t have the technology, or even more importantly, don’t have the real estate sales to bolster it, they are going to be probably the ones who bust over the next half century.

You mentioned real estate being a big part of this equation. When did the ski industry begin to bring up more environmental concerns for folks? Was there a distinct turning point maybe when it became kind of less about recreation and more about real estate?

There’s not one single event, but largely it parallels our concerns with issues of suburban sprawl in the 1950s and 1960s, because a lot of these ski resorts, if you look at them, parallel the suburban growth of the country. In fact, condominiums are really just another version of that kind of one-family track home that dominates the suburban landscape. And so it was that sort of growth, that increasing awareness within the country of things like air pollution, water pollution, wildlife impact calls and demands for the preservation of wilderness that all sort of started targeting the ski industry. They weren’t the primary target for a while, really until the late 1960s in Colorado. And the event that kind of shifts it more to that is when Colorado or specifically Denver was awarded the 1976 Winter Games. And then all of a sudden, all these concerns of the previous decade or two come to a point where we’re now going to invite the world in. We’re going to overdevelop. We’re going to have too many people living in Colorado. And it’s all so that we can build more ski resorts and service this industry, which is changing the very fabric of our state, and we don’t like it.

I think we were the only state that’s ever said no to the Winter Olympics.

Yeah, this story is really a fascinating one and one that plays at the core of the book. In the late 1960s, the Denver Olympic Committee — this group of largely businessmen and kind of elites — finally was able to win the bid to have the Winter Olympic Games. And the Winter Olympic Games was a bit of a controversy internationally in that a lot of the people in the IOC saw it just as a way to boost their tourism to places like St. Moritz and not really a viable amateur sporting event like you would have in the track and field events. Needless to say, Denver was awarded it and they failed to tell the voters. And so, the voters largely learned about the event by reading in the paper and they were surprised to learn we’re going to host the world and we’re going to dump millions of dollars into building interstates and stadiums and new sorts of venues. And they started asking questions about who’s going to pick up the tab. Along with that, how is this going to drive growth and impact on our environment, which is what we’re trying to sell for the Olympics. That we have this really amazing mountain climate, good snow and good people and deep heritage. But this was going to erode. That very thing was the concern.

By 1971, 1972, you have this massive political movement led by people like eventual Gov. Dick Lamm, who are adamantly against the Olympics. They see them as an economic boondoggle. They see them as an environmental boondoggle. They see them as a threat to the diversity of Denver specifically. And so, Colorado voters voted down hosting the games. And as you mentioned, this is the first and only time that a city has been awarded the hosting of the games and then turned down.

In the book, you examine the major changes in public land management in the American West. During the last century, the Forest Service was actually really slow to embrace the move toward more recreation, seeing more value in timber and grazing. What was it that changed their minds?

At the center of all this, we’ve been talking a lot about the ski industry and real estate, but public lands play an absolutely critical role in this story, specifically the U.S. Forest Service, because that’s where all these resorts largely built on, U.S. Forest Service land. And the Forest Service’s own history kind of prejudiced it against recreation early on. It’s established in 1905 out of the Progressive Era. It focuses on scientific management of timber and grazing and watersheds.

Recreation is a thing on U.S. Forest Service lands prior to World War II but is not a large enough issue for them really to grapple with, and their financial backing is not based upon recreation, it’s based upon selling timber feet. And so, they have this kind of bias towards timber and grazing that are paying the bills for recreation continues to grow through the 1930s, so that by the 1950s and 1960s it booms across the country. And skiing is just one example of a lot of this. So, the Forest Service is forced to grapple with, how do we deal with all of these people going on all these lands. Ski resorts have become a really efficient way to do this because you can give a permit to a ski resort. They have a boundary; they pay fees to use that. So, it’s very much in the same line as you would have with a timber permit or a grazing permit. It’s a single point of contact with the public. In fact, for as much of a story as we’re talking about, only 1/10 of 1% of all national forests are actually ski resorts to put that in perspective. And the Forest Service really struggles throughout the mid-part of the century on how to manage this, and what is their role in managing these resorts and in the White River National Forest where Vail sits.

They had decided that they could control lift ticket prices, that they would literally have Pete Seibert come in, hat in hand, and ask if he could get a nickel or 25 cent bump in lift ticket prices for the coming season, and they would try to figure out what was a fair share. Because they were coming from the idea that these are public lands that should be accessible to all the public and therefore should be fairly affordable. That idea within the White River National Forest remains in place until the late 1970s, when they’re deregulated, and lift ticket prices do what they do within free markets, and they went up 300% the first year. And then within a couple of years they were far in excess of what they had been in the mid-’70s. The Forest Services’ role now largely is in permitting and environmental regulation. So anytime that there’s an expansion, they’re the ones who oversee the environmental impact statement, they make sure that the skiers live within the bounds of the law, both environmental law and the permit. So, they’ve become more of a regulatory agency at this point. They still struggle with that mission. The Forest Service doesn’t put as much money or personnel or talent towards recreation nationwide as they do towards timber or wilderness or any of these other issues, fire obviously being the largest one, talking about climate change. So, it’s still a fraught relationship to this day.

You mentioned the idea of access that was really important with the ticket prices. That’s really changed. I think skiing has become something that’s not as accessible.

Skiing is at once more accessible today than it has been for a long time, but also, it’s pretty expensive. It’s accessible in that these sort of massive mountain passes, these Ikon and Epic passes are not excessively expensive for that kind of core user of upper middle-class folks. In fact, that’s one reason why they’re so popular. You spend $700-$800 and you get access to mountains all over the world and they sell them in just massive numbers. But for a family of vacationers or anyone who is making money below that, having access to these things is getting harder and harder. Not only do you have to buy the ski pass, which is one thing that may or may not be affordable, but then you get to rent skis and for a family of four, that’s pretty spendy. You’ve got to get to the ski area. So, there’s an automobile and gas. If you are spending the night, there’s lodging. Then if you eat on the mountain, sometimes you have to get rid of your child’s college tuition to afford a hamburger. I made the mistake of actually putting numbers to that in the book. And that lasted all of six months before those numbers changed. So, it is increasingly inaccessible to a larger number of Americans, but there’s an increasing number of people going to ski resorts at the same time.

Historically, we’ve had this argument, largely by environmental groups, that skier numbers have flattened, which is true if you look at national trends. But if you look at Colorado trends, those numbers have continued to grow, and that’s largely because we have better snow than the Southeast, where the skiing has kind of faded away, the Northeast has some bad years and then Europe, where there’s no snow this year. So, it’s a much more complex and uneven sort of story than to say, yeah, ski passes at the window cost $250 there for an open ski. It’s a lot more complicated than that.

There was a quote in the book: “Desiring to meet the public’s seemingly insatiable thirst for skiing. The Forest Service often endorsed the development of newer and larger ski resorts, but then struggled to keep up with the ski industry’s mercurial pace of growth.” Was that when private developers became such a major force within the industry?

Skiing became a vehicle for real estate sales, which then, of course, has led to the kind of growth of a lot of ski towns in the Western Slope. So not just Vail Valley, but places like Steamboat, Crested Butte, Pagosa Springs, and even my hometown of Winter Park is unrecognizable from what it was 50 years ago. And developers have become kind of the driving economic force in these areas because these are desirable places to go and live and also vacation. And we can make money off of not just condos, but other larger houses. And that has had its own environmental consequences. In fact, I really make the argument that the larger environmental impacts are not the ski runs and not all the millions of people going skiing. It is actually the sprawl that we see around ski areas and the costs of that sprawl both on local communities and their heritage, their environment and their water quality, and access to health care. These elements are all largely driven by developers, and the Forest Service has really always interpreted itself as it doesn’t have any legal means to regulate. It’s not within their purview to regulate. We approve a ski resort. We know development is going to happen, but we can’t think about that development in our decision, which historically to a lot of critics has been wrongheaded.

If you look at the mid 1970s and Dick Lamm’s campaign for governor, he says really explicitly that we have to think about this. And in fact, the state legislature changed laws so that before you can develop, you had to go through a whole bureaucracy at the state level to try to rein some of this back. Yet I don’t know if it worked. You go up in the hills today and it feels like you’re driving through one solid suburb from Golden all the way to Gypsum.

It’s interesting because it also has created this problem of the people that work in these towns cannot afford to live in these towns. So, they have to live an hour’s drive away and commute.

So, if you look at some of these early, especially in the 1960s, when you see that first flush and boom, it’s not only providing jobs for locals that is replacing some of the more extractive industry jobs of ranching. They’re still ranching on the side, but then they’re running a ski lift. It’s also attracting a whole new wave of people to come and live in these communities. And these are largely working-class families that were able to move to these places. I interviewed a guy who ended up becoming vice president of Winter Park and he said it was great in the 1970s. You can move here, ski a little bit, drink a little beer and raise a family, and it was just a really nice place to be. That, of course, starts attracting more and more people.

Then the economics shift in the 1980s, and it becomes more and more difficult for people to live there. For locals to stay in place and then for them to find workers. And so, you start seeing people commuting further and further out, coming in from Leadville, coming in from Kremmling to work at these different resorts.

One of the more interesting stories out of this was Winter Park. So Winter Park is a Denver city park, which most people don’t know. It was established in 1940 by the city park manager of Denver, a guy named George Cranmer, as part of their mountain parks system. And it had a nice simple rope tow and they put a couple of key tracks on it, and it was pretty low key. People could take the train; the famous ski train was actually how people got there. They will drive over the pass. But after the war, the industry starts to grow, and they realize in the 1950s that the city of Denver doesn’t have the capacity to run a large ski resort. And so, they hire a nonprofit board to run it, though they’re still part of the city, so it doesn’t pay any taxes. It’s a nonprofit entity that is a part of the city, but it’s wholly housed within Grand County. And that’s fine for a long while. But what happens is over time, they become the primary economic driver in the valley, if not in the county. And they are not paying for things like schools and emergency care and all this stuff that they’re bringing into the valley. So much so that by the 1980s and 1990s, the county sues the city over this, saying you need to sell this whole area. The city declines selling because the mayor at the time, a guy named Willington Webb, had already had a political fiasco over Denver International Airport not opening on time. He didn’t want to be known as the guy who messed up the airport and lost the ski area. So that’s not being sold. The county loses in court. The ski area does pay some taxes, sales taxes largely out of its new village, but that dynamic really shapes that whole local community. You know, this is our local mountain, but we kind of have been colonized by the city of Denver, and that’s unique to Winter Park. But that dynamic is, as you’re mentioning, very much the same in a lot of these resorts where the resort is really interested in its own economy and its own development. And that may not be in line with what local communities want. Look at Crested Butte and the stories that have unfolded there. We’re trying to preserve that town. It has very similar dynamics.

The landscape designer, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., who was hired in 1913 to design the Mountain Park system, was dedicated to the idea that the goal of parks was to preserve scenery and historic integrity. And I wondered, how do you think he would feel about how things kind of ended up today?

Wow, what a great question. I don’t believe that he would be that excited about the crass commercialism that drives a lot of these sorts of resorts. I think he’d be in awe at the scale of recreation, not just within skin history, but within his mountain parks and how that is what he foresaw as a very valuable component to living in Denver, that we have these hinterlands that have these remarkable landscapes. And so that has come true up and down the front range that we love to go and play in our hills. But the ski industry, I think, is something that is so large and so much different than what he could have ever envisioned in terms of the amount of money that’s involved with it, the scale of people that yeah, I think he’d be both thrilled at one point and then like a little in disbelief, maybe critical in the other side of it.

Your book ends by tracing the history of radical environmentalism from the 1960s up to the Earth Liberation Front’s 1998 Arson at Vail Ski Resort over the planned Category Three expansion. It was the largest “eco-terrorist attack” in the United States, causing more than $12 million in damages. But the attack kind of backfired, driving sympathy for the resort more than it called attention to the cause. In the end, Vail ended up opening what is now the Blue Sky Basin. Looking back now, what are some of the ripples that continue from that time to today?

We still are not as critical of the ski industry as we probably were at that time. You know that story really highlighted to me what was at stake within the ski industry. It’s a great narrative device to introduce the story. You got a guy running across the ridge setting fire with basically cans of napalm. But why would Vail, a ski area, be the target of this sort of attack? When you think of all the other environmental issues that are especially in the West, So it highlighted that and kind of this idea of the role of capitalism and the environment that is the critique of a lot of radical environmentalists where they really look at this role of developers and capital, and they’re saying this is the cause of our problems. Ski resorts are a great example of that. But really, like, as you mentioned, that arson, that attack flipped the script where Vail went from being the bad guy who was going to develop this habitat for the Canada Lynx, a threatened species, and more importantly, one of the largest elk herds in the state where their birthing grounds were, to being the victims and the good guys because they’ve been attacked by terrorists, which is a problematic term to begin with. Since that moment, we have not seen the same sort of vitriol or condemnation of the ski industry about its environmental impacts. So, it has kind of shifted some of that dialog. When we do have these sorts of criticisms now, it’s about growth and gentrification and chasing locals out and who can afford a $3 million condo on the side of a ski hill, which is a radically different sort of conversation than wildlife impact. It may be something that comes to a head again. There are ski resorts who are going to expand in the future, and we are seeing increasing wildlife interaction up and down the front range of Colorado and throughout the Western Slope with mountain lion attacks. The reintroduction of wolves is going to do some interesting sorts of things. So that possibly could bring this back to the forefront in the same way that it was in the nineties. But I really do think that that event changed the conversation a lot.

Michael Childers

Michael Childers is an associate professor of history in the College of Liberal Arts at Colorado State University, specializing in the environment and tourism, including the history of outdoor recreation, world environmental history and American environmental history. He’s also the author of Colorado Powder Keg, which examines the history of Colorado’s ski industry along with the challenges brought by the industry’s meteoric growth — from finding balance regarding the private development of public lands to the increasing environmental concerns over wildlife management, and air and water pollution.

Childers is currently writing his second book, tentatively titled, “The Mountains are Calling: Tourists and the Unmaking of Yosemite National Park,” examining the park’s history through visitors’ own experiences, and the environmental costs that occur when a place becomes too popular.

The Audit

Recorded at the KCSU studio, Colorado State University’s new podcast, The Audit, features conversations with CSU faculty on everything from research to current events. Just as auditing a class provides an opportunity to explore a new subject or field, The Audit allows listeners to explore the latest works from the experts at CSU.