Researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Colorado State University have identified the oldest decisive evidence of humans’ close evolutionary relatives butchering and likely eating one another.

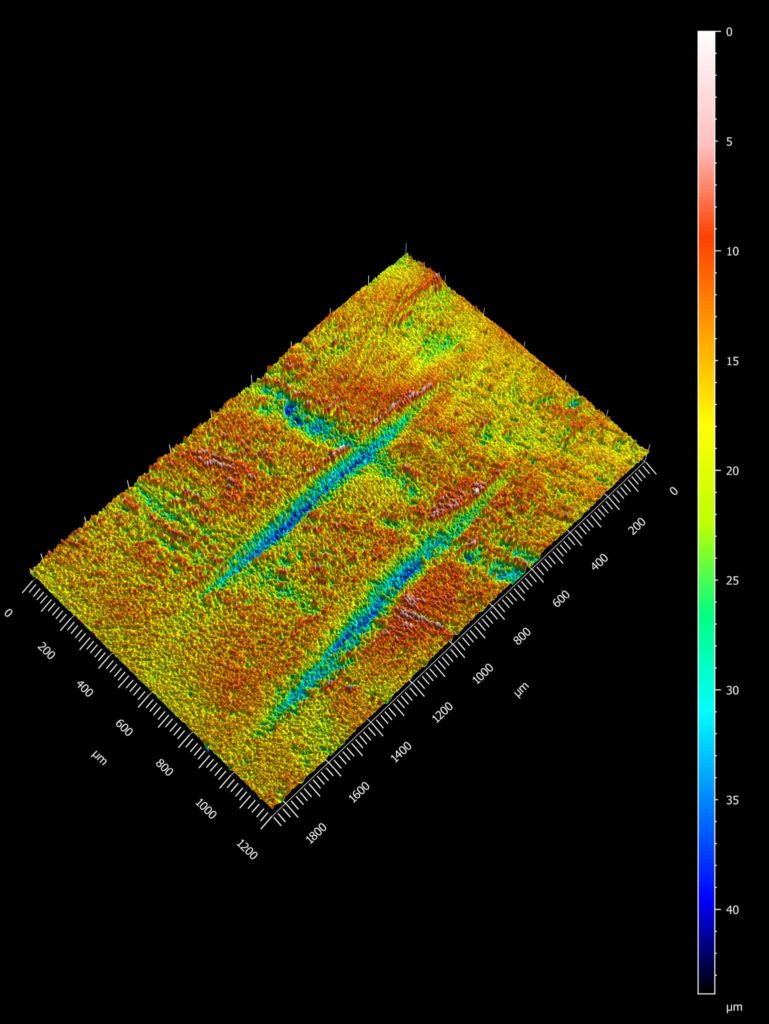

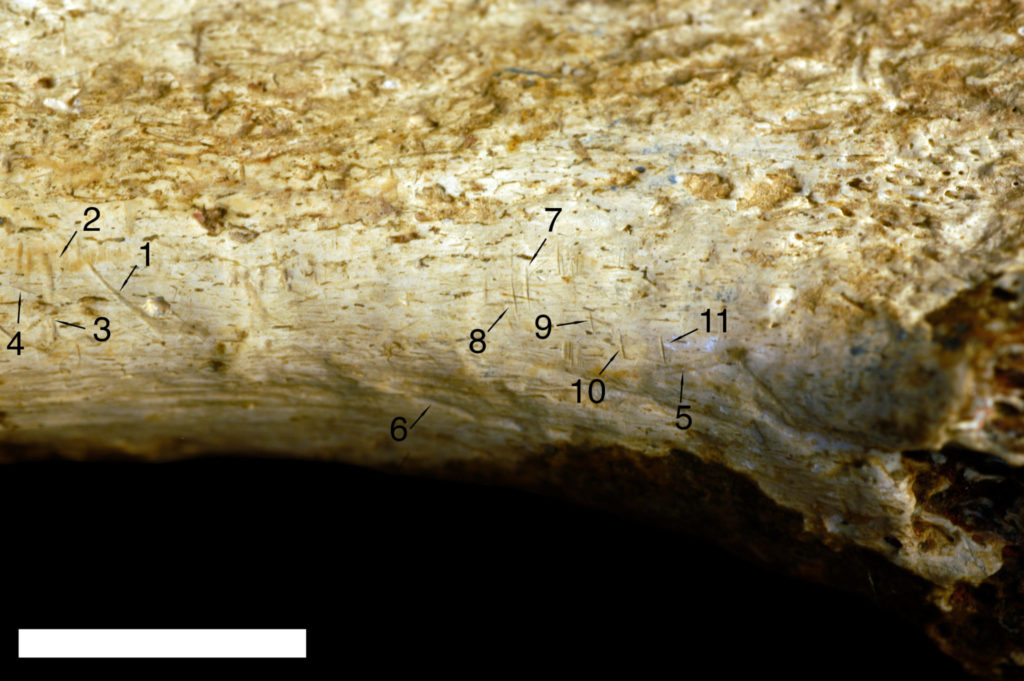

In a new study published June 26 in Scientific Reports, National Museum of Natural History paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner and her co-authors, including paleoanthropologist and CSU Associate Professor Michael Pante, describe nine cut marks on a 1.45-million-year-old left shin bone from a relative of Homo sapiens found in northern Kenya. Analysis of 3D models of the fossil’s surface — completed by Pante — revealed that the cut marks were dead ringers for the damage inflicted by stone tools. This is the oldest instance of this behavior known with a high degree of confidence and specificity.

“The information we have tells us that hominins were likely eating other hominins at least 1.45 million years ago,” Pobiner said. “There are numerous other examples of species from the human evolutionary tree consuming each other for nutrition, but this fossil suggests that our species’ relatives were eating each other to survive further into the past than we recognized.”

The research is the first application of the 3D quantitative method — developed and published by Pante in 2017 — to a fossil specimen.

“It marks a new standard for mark identification on bones that is more objective and reliable than the qualitative approaches used in the past,” said Pante, who has done extensive work studying the feeding behavior of early members of the human genus (Homo), particularly in Tanzania where many important discoveries about the evolution of human hunting have been made.

A telling cut

Pobiner first encountered the fossilized tibia, or shin bone, in the collections of the National Museums of Kenya’s Nairobi National Museum while looking for clues about which prehistoric predators might have been hunting and eating

humans’ ancient relatives. With a handheld magnifying lens, she pored over the tibia looking for bite marks from extinct beasts when she instead noticed what immediately looked like evidence of butchery.

To determine if what she was seeing on the surface of this fossil were indeed cut marks, Pobiner sent molds of the cuts — made with the same material dentists use to create impressions of teeth — to Pante with no details about what he was being sent, simply asking him to analyze the marks on the molds and tell her what made them.

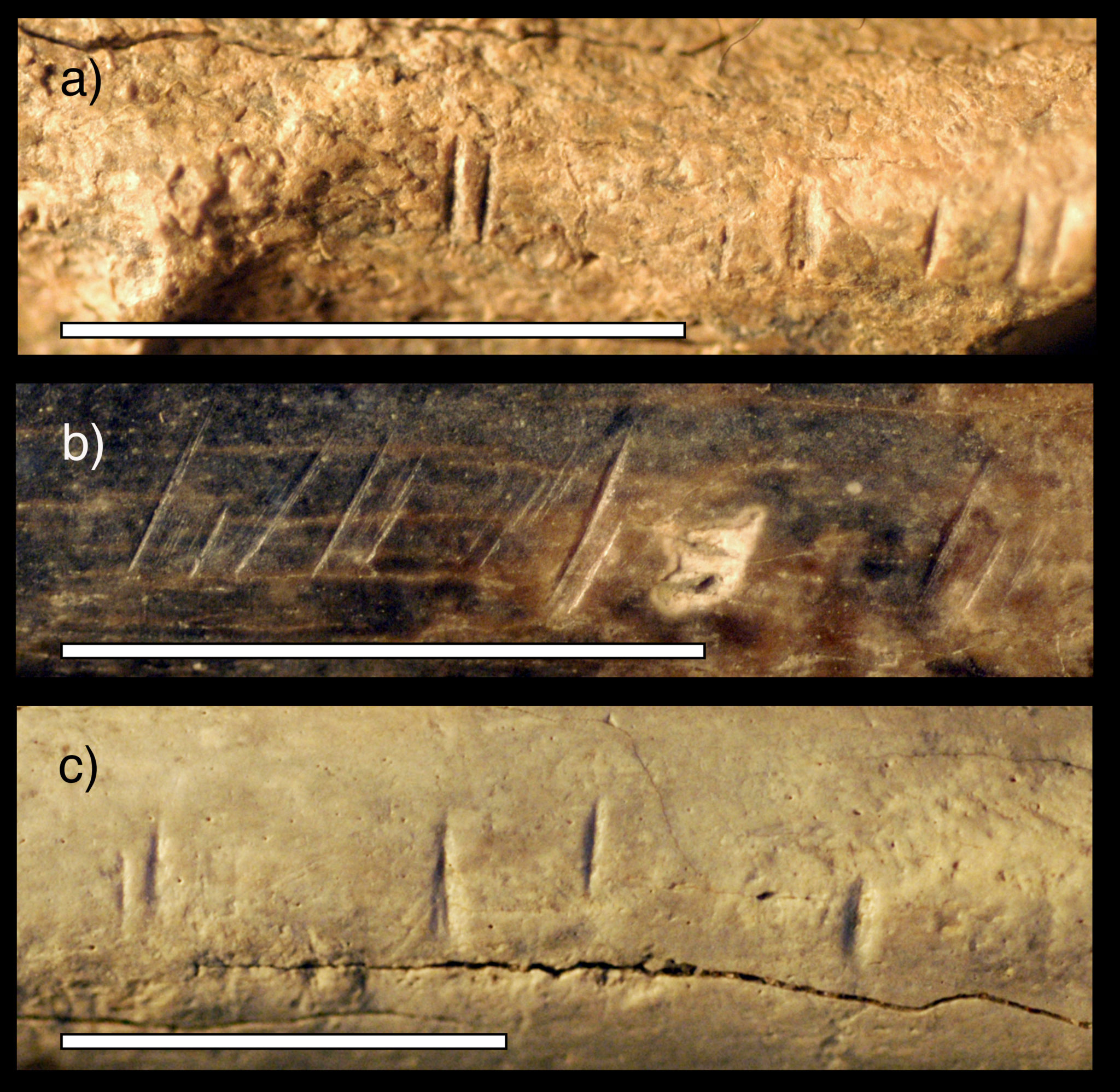

Using a 3D non-contact profilometer to create extremely precise scans of the molds, Pante then compared the shape of the marks to a database of 898 individual tooth, butchery and trample marks created through controlled experiments.

The analysis positively identified nine of the 11 marks as clear matches for the type of damage inflicted by stone tools. The other two marks were likely bite marks from a big cat, with a lion being the closest match.

According to Pobiner, the bite marks could have come from one of the three different types of saber-tooth cats prowling the landscape at the time the owner of this shin bone was alive. However, she said the cut marks look very similar to those seen on other animal fossils that were being processed for consumption.

A case of cannibalism?

While by themselves, the cut marks do not prove that the human relative who inflicted them also made a meal out of the leg, it is the most likely answer rather than as a ritual or a defensive mark during a fight, Pante said.

The marks are in a location where multiple muscles attach and are consistent with defleshing marks observed on animal fossils from the same region and time period, he noted. A weapon strike would likely be a single impact and much deeper, and there is no current evidence for that type of weaponry from this early in the archaeological record.

While this may seem like a case of cannibalism, Pante noted that there were multiple hominin species around at 1.45 Ma (mega annum or “millions of years”). Meaning that even if this was a case of consumption, it may not actually be cannibalism — which requires that the “eater” and “eaten” both be of the same species — but instead anthropophagism.

The fossil shin bone — originally found by Mary Leakey — was initially identified as Australopithecus boisei and then in 1990 as Homo erectus, but today, experts agree that there is not enough information to assign the specimen to a particular species of hominin. The use of stone tools also does not narrow down which species might have been doing the cutting. Recent research from Rick Potts, the National Museum of Natural History’s Peter Buck Chair of Human Origins, further called into question the once-common assumption that only one genus, Homo, made and used stone tools.

So, while this fossil could be a trace of prehistoric cannibalism, it is also possible it was a case of one species chowing down on its evolutionary cousin.

None of the stone-tool cut marks overlap with the two bite marks, which makes it hard to infer anything about the order of events that took place. For instance, a big cat may have scavenged the remains after hominins removed most of the meat from the leg bone. It is equally possible that a big cat killed an unlucky hominin and then was chased off or scurried away before opportunistic hominins took over the kill.

Regardless of how this research may impact the current narrative regarding how our early ancestors interacted, Pante said we should not be too hard on them.

“Our ancestors likely did anything necessary to survive, including eating each other,” he said. “Hominin fossils are very rare, and most are not studied for butchery marks so potentially there are other currently unknown examples in museum collections.”

A debate of the ages

One other fossil — a skull first found in South Africa in 1976 — has previously sparked debate about the earliest known case of human relatives butchering each other.

Estimates for the skull’s age range from 1.5 to 2.6 million years old. Apart from its uncertain age, two studies that have examined the fossil (the first published in 2000 and the latter in 2018) disagree about the origin of marks just below the skull’s right cheek bone.

One contends the marks resulted from stone tools wielded by hominin relatives and the other asserts that they were formed through contact with sharp edged stone blocks found lying against the skull. Further, even if ancient hominins produced the marks, it is not clear whether they were butchering each other for food, given the lack of large muscle groups on the skull.

To resolve the issue of whether the fossil tibia she and her colleagues studied is indeed the oldest cut-marked hominin fossil, Pobiner said she would love to reexamine the skull from South Africa, which is claimed to have cut marks using the same techniques observed in the present study.

She also said this new shocking finding is proof of the value of museum collections.

“You can make some pretty amazing discoveries by going back into museum collections and taking a second look at fossils,” Pobiner said. “Not everyone sees everything the first time around. It takes a community of scientists coming in with different questions and techniques to keep expanding our knowledge of the world.”