Food has always been the great unifier. We gather around the table and work things out by breaking bread.

For the students in Colorado State University archaeology/anthropology instructor Emily Wilson’s class, Archaeology of Ancient Roman Food, food is teaching them a lot about what has – and hasn’t – changed in the past 2,700 years.

Ancient Romans – they’re just like us

“As a teacher, I’m always trying to bring the ancient world into the classroom in a way that’s not just talking about what separates us from them,” Wilson said. “When many people think about the ancient world, they don’t tend to consider the people as being really real because of the vast chronological gap. And the truth is they were exactly like us. They had the same hopes and concerns. My primary goal is to make this world real to my students.”

That message hit home for senior anthropology major Kayla Spahr when she prepared Panis Quadratus, a traditional Roman sourdough bread.

“As a bread baker, it was amazing to see how little bread baking has changed,” Spahr said.

Panis Quadratus is one of the few ancient foods that we know what it looked like thanks to the excavations of Pompeii. Archaeologists discovered paintings of the bread and ovens still containing carbonized loaves, which were round and segmented into eight pieces with a hole in the center.

“To actually be able to see what the food looked like, replicate it and taste it was amazing,” Spahr said.

Ingredient by ingredient

The class begins by looking at various ingredients and the archaeological evidence surrounding it, where it was found, how it was processed, how it was consumed and by whom.

One of the most important ingredients was wheat, Wilson said. Bread constituted 60%-70% of the average Roman diet, with the Roman state providing bread for its citizens via a grain dole.

“Bread was the substance that basically built Rome because a lot of Roman citizens were on this bread and grain dole,” Wilson said. “It powered many of the massive monuments of Rome like the Colosseum and the Ara Pacis and the Forum of Augustus because the Roman poor were employed to construct them, and they were the ones on this grain dole.”

Food also becomes the gateway to talk about larger issues such as social hierarchies.

The Roman elite had access to more variety and higher quantity and quality of foods, including things like spices and meats such as flamingo, Spahr said. Meanwhile, the lower classes relied on the grain distribution to survive.

“It made me realize that though we have different technologies, the tradition of food accessibility goes back a long way and is still here,” she said. “No matter how much we romanticize the Roman Empire or glorify our present technology, food has always separated social classes.”

Recipe for flamingo from “De Re Coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking”

Pluck the flamingo, wash, dress, tie the legs together, place in a saucepan, add water, salt, dill and a little vinegar. When cooked halfway, make a little bundle of leek and coriander and let it cook (with the bird). When it is nearly cooked, add wine that has been boiled down to give it color. Combine in a mortar pepper, caraway, coriander, asafoetida, root, mint, rue: grind; moisten with vinegar, add dates, pour over some of the cooking wine. Pour it into the same saucepan, thicken with corn flour, pour the sauce over the bird and serve. The same recipe can also be used with parrot.

The joy of cooking

The students analyze various aspects of cooking – from methodologies to menus – as well as dining traditions and table manners.

“There’s only one example of an ancient cookbook from Rome, and it’s not even really what we would call a cookbook,” Wilson said. “De Re Coquinaria (“On the Subject of Cooking”) features recipes, but the recipes are not meant to be a step-by-step guide for a cook to create a specific dish; they don’t even have measurements for the ingredients. Rather, this is a book written by an elite individual who never set foot in the kitchen; enslaved people would have prepared all of the dishes.”

The textbook for the class combines recipes from this cookbook and other Roman sources concerned with preserving foodstuffs, and the students choose an ancient Roman dish to prepare as closely to the original item as possible as an assignment.

“I ask them to cook it with as few modern gadgets as possible,” Wilson said. “They can’t use blenders; they can’t use air fryers. They can have water in a bowl, but they can’t use running water. They can use their oven, and they can use their stove.”

The goal is to have them reflect on how the process differs from today, as well as the taste.

“These dishes aren’t as flavorful as we know them today because spices were expensive in the Roman world, and most people didn’t have much access to spices or even salt,” Wilson said. “In fact, the word ‘salary’ comes from the Latin word for ‘salt.’ And that’s because some people got paid in salt. It was much rarer back then.”

Convivium

A dining event or gathering in the Roman world was called a convivium, a “living of life together,” Wilson said. While we still hold on to that tradition, it’s been somewhat fragmented in today’s society of stopping at McDonald’s and eating a hamburger in the car.

“For the Romans, dining very much was an event that focused on community,” she said. “Not just everyone coming together and sharing a meal, but creating and reinforcing those social bonds, those bonds of friendship but also of obligation.”

Attending a nice dinner at someone’s home would put you in their debt to invite them to dine at your home or pay them back in some way; alternatively, it would acknowledge a debt that couldn’t be paid and reinforce a patron-client relationship.

“Everything in the Roman world was so much a part of community that was fundamentally supported by that foundation of Romans harvesting the land, raising pigs or cows, pressing grapes to make wine,” Wilson said. “All of these things that in our world we’re so disconnected from because we just go to the grocery stores and purchase food grown in Argentina or California, out of season and part of industrial agriculture. So, it’s this entire community of people who pitch in and have a role in bringing food to your plate.”

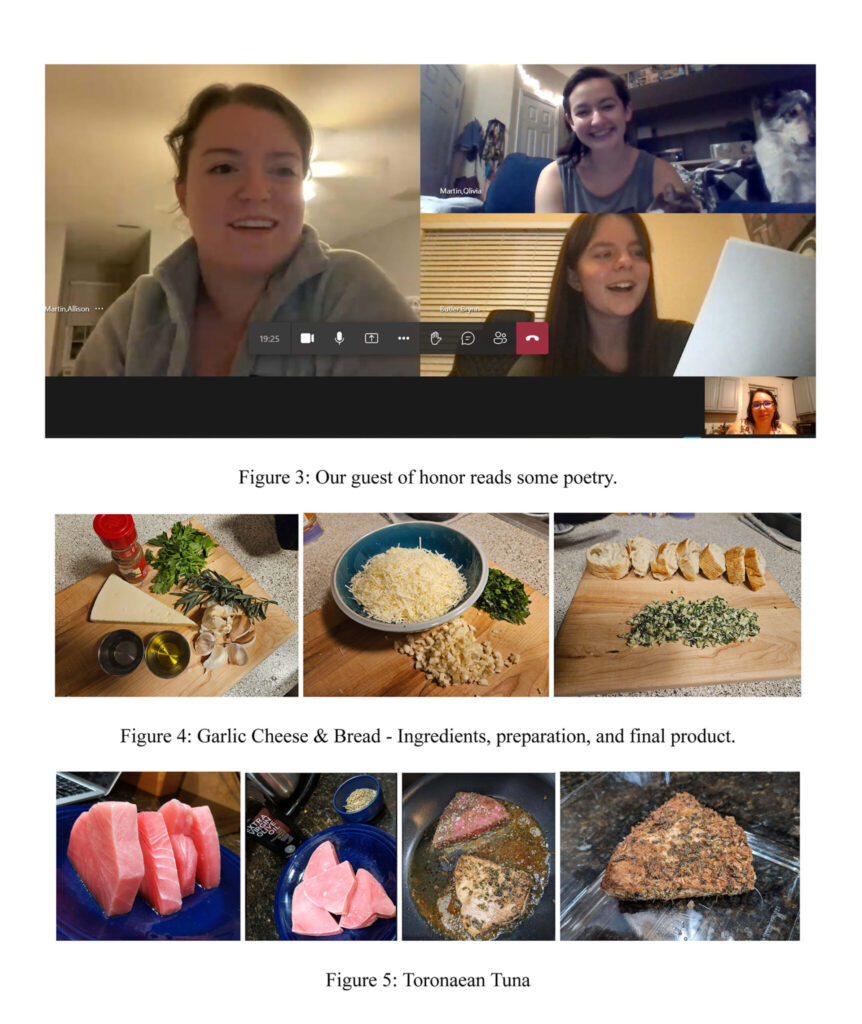

For their final project, the class breaks into groups and has a one-hour convivium, with each student assigned a particular role – host, guest of honor, client seeking a favor. It’s a little tricky because this is currently an online course, but Wilson said she hopes to make it in-person for future classes.

Afterwards, they collaborate on a paper reflecting upon the experience, noting everything from the atmosphere to the food preparation to the conversation.

“They’re thinking through what it really means to ‘dine like a Roman,’” Wilson said.