On the east side of Palacio de La Moneda, in Santiago, Chile, sits a wooden door. The door’s bright amber wood slates and adorning alloys distinguish itself from the ashen outer walls of La Moneda. To the left of the door is the number 80. Known as Morandé 80 for its physical address, it was constructed in 1906 as an informal entrance for Chile’s president to enter La Moneda, the seat of the presidency and several cabinet offices.

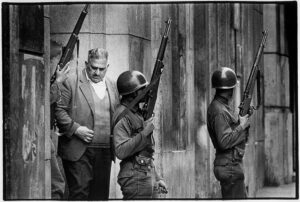

Right: General Augusto Pinochet

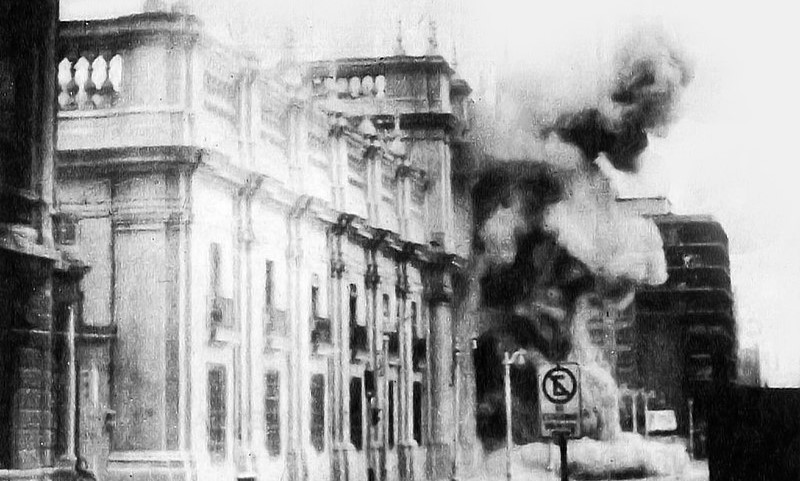

On Sept. 11, 1973, democratically elected President Salvador Allende’s body was carried out of Morandé 80 following his death by a self-inflicted gunshot. His death came after a morning of bombing from the Chilean Air Force on La Moneda and its capture from a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet.

The next day, Pinochet assumed power of the military junta, beginning a 17-year-long dictatorial rule of Chile marred by human rights violations, censorship, social stratification and a political divide still felt in Chile today.

A new reality

“What was Sept. 11, 1973, like?” Assistant Professor of Spanish Carmen Martin Quijada said. “It’s like you woke up in reality and by noon it was a different country with tanks on the streets and bombs.”

For Martin Quijada, who grew up in Chile after the coup, its legacy and Pinochet’s regime was not something regularly discussed at home or school. The textbooks they used mentioned the government as the “military government.”

At home, part of Martin Quijada’s understanding and interest in the regime and the consequences for Chileans came from the discovery of cassette tapes in her mother’s closet, which included artists like Argentian folklorists such as Mercedes Sosa.

“Consider in all of these [Latin American] countries, they all have dictatorships at this time, in Argentina it was Videla,” Martin Quijada said. “This is the voice [Sosa] that I connected with this discovery. Then, I started exploring Chilean groups.”

Though these artists Martin Quijada came across varied in their political activism, many had long been exiled, killed or were “disappeared.” Like folklorist Victor Jara, a supporter of Allende and leftist activist, who was among the first wave of tortures and executions at the hands of Pinochet’s soldiers. He was killed on Sept. 12, 1973.

Such injustices were and continue to be commonplace in the reverberations of Pinochet’s rule. An estimated 3,000 to 5,000 people were killed because of the politically motivated violence under Pinochet, and it’s estimated between 1,000 and 3,000 people were disappeared becoming known as “desaparecidos.”

Looking back

Specializing in the study and analysis of Latin American literature, Martin Quijada has spent much of her academic career examining the work of Chilean authors like Alia Trabucco Zerán, Raúl Zurita, Nona Fernández, and how these authors capture and convey the times under Pinochet, connecting Chileans back to the history.

“In all these texts where it says things like ‘after the time,’ ‘at the time,’ or ‘looking back,’ it’s an archive,” Martin Quijada said. “All of those texts hold the memory and testimony of a time, and they prevent the time and the people from being forgotten.”

Chile’s desaparecidos have left perhaps the most far-reaching ripple in Chilean’s lives. To be “disappeared” meant not only to be kidnapped, but to have all traces of your final moments as a citizen and prisoner erased, with no body to be found and no answers for families left behind.

The steps prior to disappearing were often official torture centers under Pinochet’s regime, where captured citizens were physically, psychologically and sexually abused. Even as more recent government efforts have been made to identify victims, misinformation and outright denial of these events have plagued Chile.

Yet in the face of such denials, Martin Quijada sees the role of art and literature in maintaining the narratives of the past for Chile and helping Chileans relate to their history.

“Literature is using memory to relate. How could we hold the theory of ‘before dictatorship’ and ‘in the dictatorship’ and the period ‘after the dictatorship’ and what would be misunderstood if it was not by the convention of literary text and just general art,” Martin Quijada said. “The higher value of that is the many people who were producing art during, before and after they were old and trying to make visible ‘the other,’ and how [the regime] committed these human rights violations.”

A new constitution

Though Pinochet’s dictatorship ended in 1988 with a vote not to extend his presidency, consequences of his rule were felt even after the official transition with the election of President Patricio Aylwin in 1990 and a series of efforts to establish a new constitution.

When the Constitutional Assembly was tasked with drafting a new constitution, it was rejected with a nearly 62% majority in September of 2022, preserving the Constitution of 1978 and its following reforms.

Many reasons are at fault for its failure, including voters who turned out for the 2022 but not the 2020 referendum, as well as the obvious divergence of political views, including continued support for Pinochet. Yet notably what stands out is the many commonalities that plague many democratic elections: lopsided political spending and misinformation.

A new assembly has formed in Chile, again tasked with a new draft to the country’s constitution, which voters will approve or reject on Dec. 17 of this year. Though Pinochet has been dead nearly as long as his time in power, Chile remains divided on his regime and its impacts, particularly as it relates to human rights and government.

“How can we not, at this point, 50 years later, have a clear view, or a clear discourse, or a clear position, on something like a coup. It’s not acceptable,” Martin Quijada said. “Regardless of the reasons, democracy must be preserved and can be fixed with more democracy and not military intervention – that’s the end of democracy.”

Carmen Martin Quijada is a published poet and professor of Spanish, specializing in the study of Spanish and Latin American Literature, including the work of Chilean authors with emphasis and analysis on Dictatorial and Post-Dictatorial Chile. Her most recent publishing can be found in Chile desde los Estudios Culturales, where she authors the chapter, “Búsquedas y recolecciones: independencia del lenguaje y la memoria de los hijos en La resta de Alia Trabucco Zerán”.